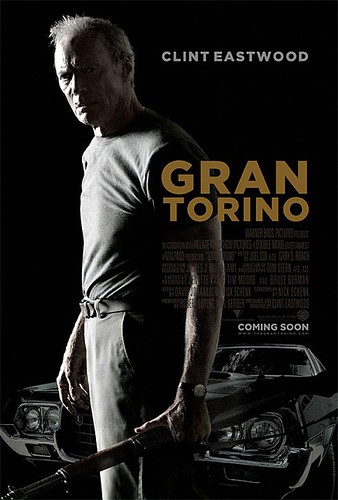

“Gran Torino,” Clint Eastwood’s latest film as director and star is being advertised as a vigilante story of one man taking on an Asian gang, but that is only one small aspect of the story that is more human than audiences might expect.

“Gran Torino,” Clint Eastwood’s latest film as director and star is being advertised as a vigilante story of one man taking on an Asian gang, but that is only one small aspect of the story that is more human than audiences might expect.Eastwood stars as Walt Kowalski, a bitter, caustic, grumpy and outwardly racist Korean War vet, who has stayed in a Detroit suburb that now largely has an Asian population. The film opens at the funeral for Walt’s wife and we are introduced to Walt’s obnoxious children and grandchildren. They represent the worst kind of Americans and Walt can’t stand them.

Walt uses every ethnic slur in the book that could be directed at an Asian, but when he inadvertently protects his neighbors from an attack by gang members he finds himself becoming emotionally attached to the people he pretends to hate. As his relationship grows with his neighbors he realizes he has more in common with them than his actual family, so much so when they are threatened he feels he must protect them.

Eastwood hasn’t been on screen since 2004’s “Million Dollar Baby,” but he’s certainly been busy behind the camera. As a director he’s had a remarkable late career surge that has him working on a level of skill he had only previously hinted at.

He has been averaging a movie a year since 2002, including two large scale war movies. Eastwood is 78 years old. It is rare to see this amount of quality output for someone a third of Eastwood’s age, but Eastwood has shown no sign of slowing down.

It is easy to see why the screenplay by Nick Schenk would compel Eastwood to get in front of the camera again. Eastwood is allowed to riff on his tough guy persona. He glares, growls and grimaces as only he can. It gets close to self-parody until suddenly the performance turns into something subtler and richer.

He intentionally recalls his most famous characters, Dirty Harry Callahan and The Man With No Name from the trilogy of Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns. He knows his screen persona is bigger than him and the way he plays towards and against the audience's expectations creates moments both humorous and moving.

Eastwood cast primarily all amateur actors to play the Hmong community. The Hmong, we are told, are hill people from Southeast Asia that fled after the Vietnam War.

Many have been critical of the Hmong actors, but the performances are largely effective. These aren’t great thespians, but they do what they are asked to do well.

The film’s central relationship is between Walt and Thao (Bee Vang) who attempts to steal Walt’s prized 1972 Gran Torino when pressured by his cousin’s gang. Walt, with great reluctance, takes the teen under his wing and tries to “man him up.”

There is also a strong relationship between Walt and Thao’s sister Sue (Ahney Her), who is both sweet and sassy. She doesn’t take any of Walt’s gruff attitude and instead dishes it back. Walt appreciates this. Of the amateur actors, Her is the real find. She’s likable and has a genuine screen presence. It would be nice to see her get more work.

There are other connections in Walt’s life. He has an amusing reoccurring back and forth with his barber (John Carroll Lynch, “Zodiac”), who like Sue goes toe-to-toe with the old man. There’s an especially funny scene where Walt and his barber try to teach Thao how to talk like a man.

There is also a young priest (Christopher Carley) who promised Walt’s wife that he would look after her husband. Walt wants nothing of it, but the persistent priest eventually breaks down Walt’s defenses. The dynamic that develops here is an interesting one and Carley, who has an assortment of bit roles on his resume, is another actor to watch.

This isn’t deeply profound storytelling, but it is a tried and true formula executed with care. The relationships that develop between Walt and Thao, Sue and the priest follow a familiar arc, but there are surprises in the details as well as a lot of warmth and humor.

It isn’t until the film’s conclusion that the retribution hinted at in the trailer is delivered. Some may be hungry for more old school Eastwood action, but because the film took the time to develop Walt and his relationships completely the final scenes are all the more powerful.

This is a redemptive story, but Walt doesn’t go through cloying, hollow metamorphosis from a mean old man into a really nice guy. That’s the key to film’s success. In the end, he still clings to his racial slurs, although now he says them with fondness.

No comments:

Post a Comment