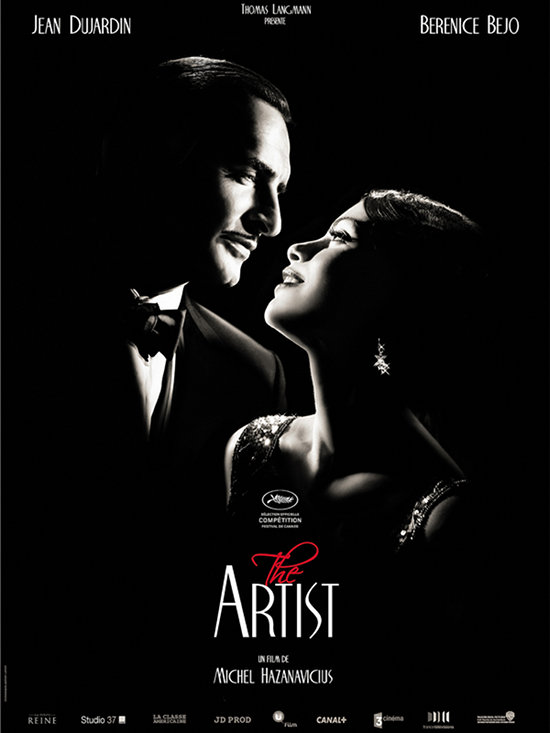

“The Artist,” the odds on favorite to win best picture at this year’s Academy Awards, is a tough sell to mainstream audiences. Not only is it black and white, but it is also a largely silent film and many modern moviegoers assume that such a film would be boring. Those who are hesitant, though, should take the leap because “The Artist” is an engaging, accessible and charming film.

“The Artist,” the odds on favorite to win best picture at this year’s Academy Awards, is a tough sell to mainstream audiences. Not only is it black and white, but it is also a largely silent film and many modern moviegoers assume that such a film would be boring. Those who are hesitant, though, should take the leap because “The Artist” is an engaging, accessible and charming film.Set during the late 1920s into the early 1930s, “The Artist” marks the transition from silent film to talkies. George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), like many silent actors of the time, goes from being a huge star to unemployed once talkies gain popularity. In his place, Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), an actress he helped get her first job, rises to fame. George struggles with his pride as Peppy offers to help him.

Of course, silent films aren’t truly silent as they have music. What they lack is spoken dialogue and realistic sound effects. This means that silent actors had to be very expressive and that the film score was even more important in getting across a sense of tone and mood. “The Artist” has an excellent score by Ludovic Bource that alternates from light-hearted whimsy to wistful melancholy. The score even quotes Bernard Hermann’s score for “Vertigo” to interesting effect.

Dujardin is an actor who seems like he was born in the wrong era. He seamlessly fits into the silent film format. He makes George part Charlie Chaplin, part Douglas Fairbanks and part Gene Kelly. With a broad smile and expressive face, he is effortlessly charismatic. He is paired with an adorable dog named Uggie who, excuse the cliche, will melt hearts.

Dujardin is an actor who seems like he was born in the wrong era. He seamlessly fits into the silent film format. He makes George part Charlie Chaplin, part Douglas Fairbanks and part Gene Kelly. With a broad smile and expressive face, he is effortlessly charismatic. He is paired with an adorable dog named Uggie who, excuse the cliche, will melt hearts.

Bejo, who like Dujardin has a bright smile and the ability to say everything with just a look, also seems made for silent film. John Goodman, who plays a movie studio head, is clearly relishing the opportunity to be broadly expressive. He has a great moment when he begrudgingly concedes to one of Peppy’s wishes.

“The Artist” does an excellent job of emulating the style of the silent film era, but some critics of the film have claimed that you’d be better off watching the classic work of Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and others.

It is true that “The Artist” doesn’t best classic silent film, but it is a good entry point. Writer/director Michel Hazanavicius is also using the silent film format to comment on silent film in a way that the originals could not.

There is a dream sequence in which Dujardin’s George can’t speak, but suddenly the world around him does have sound. It is brilliant allegory for the transition from silent to sound movies. Many actors could no longer work because they had terrible speaking voices. Ironically talkies silenced them.

“The Artist” also gets to add more modern acting techniques to the silent format. While the actors do perform broadly in many cases, there also moments of quiet introspection that seem to be more a reflection of today’s acting styles. It is fascinating to see the two acting styles working so well next to each other.

One of the other joys of “The Artist” is a dance sequence that recalls the work of Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire. Modern dance scenes are highly edited, but Hazanavicius shoots his dance number like they used to: one long take with the actors in full frame so you can see their every move uninterpreted. Dujardin and Bejo aren’t flawless dancers, but it is a wonderful sequence because, like the rest of the film, it is a reminder of a time not quite forgotten.

“The Grey” is being advertised as Liam Neeson versus killer wolves, which does a disservice to the film. This is a intense, emotional journey of a group of men trying to survive in the harsh Alaskan wilderness.

“The Grey” is being advertised as Liam Neeson versus killer wolves, which does a disservice to the film. This is a intense, emotional journey of a group of men trying to survive in the harsh Alaskan wilderness.